There exists an imperialist perspective that to climb is to conquer. To have successfully summited a mountain is akin to victory - where man dominates natural creation.

To climb, though, is not to conquer but rather to cooperate. From seasoned alpinists who have trained for years to summit the low-oxygen snow-encrusted spires of K2 on the border of China and Pakistan, to the humble gray mouse lemur that scales the arid forests of Madagascar each day for food: climbing comes from an understanding of the natural features before you. It involves an understanding of your capabilities and shortcomings, and then a concerted effort to adapt yourself to the challenge of the vertical terrain.

The relationship between rock and man and rock and animal innately creates a hero's journey; a passage that encompasses conflict, introspection, and a triumph over the adversity of nature’s natural formations. It is this very struggle that unites all climbers in their desire to look inward and find the strength to overcome challenges, primarily through hard work and self-sufficiency. It acts as a stark barometer of who you are and what you can do.

This natural desire to better understand our bodies to optimize for performance is pervasive through all athletes. Having climbed since I was 12 years old, I have always been fascinated by how my body fluctuates temperamentally based on the type of sport I threw myself into - almost as volatile as my behavioral mood swings through puberty. An increase in cardio thins out my limbs. They become leaner and more tubular with less definition. Replacing cardio with endurance climbing makes my upper arms and shoulders swell up while my chest loses fat and my pectoralis muscles become more defined.

To study climbing, I investigate how the Rocky Mountain goat is biologically engineered to survive and thrive through climbing in its extreme habitat. I seek, through scientific illustration, to find a visual explanation for this cooperation of man, animal, and nature on the wall.

Happy adventures.

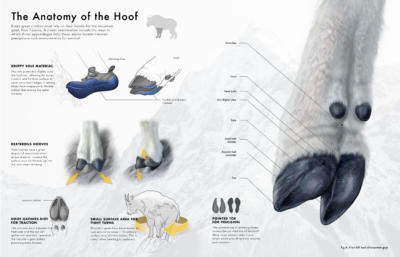

Of all the phenomenal animals that climb out of life necessity, none scales sheer rock faces with such endurance like the Rocky Mountain goat, otherwise known as the oreamnos americanus. Growing up to a hefty 140 kg large, the mountain goat is the largest mammal of the ungulate family (any members of a diverse group of primarily large mammals with hooves) whose habitat resides primarily on the steep 60+ degree slopes of the Rocky Mountains in North America.

How do these seemingly cumbersome creatures manage to exist in such harsh climates with such unforgiving terrain? Compared to man who has significantly higher body flexibility both in core and their digits, the goat has relatively low limberness. Their shoulders stabilize their load-bearing legs, but abductive movement abilities are limited.

How do they compare to us and our abilities to scale vertical featured terrain, and what can we learn about our bodies by understanding our high altitude animal neighbors'?